Comparing Literature

[This tutorial was first published in 2006. It attempts to bring some other poets from non-British backgrounds to the fore, and asks users to question their own inherent prejudices. To most people in English-speaking countries the German, Turkish, or Austrian soldier is an unknown quantity, vaguely referred to in some of the poems. Yet what sentiments were the poets from those countries attempting to express? Similarly, even though they were allies during the War, the poetry of the soldiers of France, Russia, or Italy are seldom read outside of their countries by the beginning student.]

Introduction to Comparing Literature

Begin by reading this short introduction to comparing literature from different nations, and the other short essays on Comparative Literature and Initial Considerations. Then go to Exercise I by following the link at the bottom of this page or in the side bar to the left. There are two exercises in this seminar, once you have completed Exercise II you have finished.

"This is no case of petty right or wrong

That politicians or philosophers

Can judge. I hate not Germans, or grow hot

With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers."

'This Is No Case Of Petty Right Or Wrong' ll. 1–4, Edward Thomas

The Great War, with its carnage of ruling class rhetoric, put paid to some of the more strident forms of chauvenism on which English had previously thrived...[literature] represented a search for spiritual solutions on the part of the English ruling class... [it] would be at once solace and reaffirmation, a familiar ground on which Englishmen could regroup both to explore, and to find some alternative to, the nightmare of history

Terry Eagleton, Literary Theory: An Introduction (1983), p. 30.

The divisions in Europe created by the Great War are still felt today. Socially, the War provided an enormous upheaval in perceptions of hierarchy and duty. It fed on existing prejudices and created new ones that are still present throughout Europe today (as witnessed in the continuing struggles in the Balkans). Many of these were later replayed in the Second World War.

First World War poetry to a degree, breaks free of many of the stereotypes one would associate with war poems, yet at the same time perpetuates many myths. On the one hand the poets presented in the previous tutorials find common cause with Thomas's sentiments expressed above. It is almost impossible to find in the poetry of Sassoon or Owen anything which could be described as anti-German per se. Sassoon, for example, does not choose to direct his anger towards the enemies in the opposing trenches but instead at the High Command or the public back home. Owen, also, chastises the war-mongers and jingoists in Britain (as with 'Dulce et Decorum est') or concentrates on the pitiful nature of the conflict. Yet at the same time the study of First World War poetry is very insular, and the tutorials in this series could also be accused of suffering from this. Nearly all of the poems presented so far have been British, and even more narrowly focusing entirely on the poetry of the Western Front.

Stuart D. Lee

Why not Comparative Literature?

It is interesting to note that the title of this tutorial deliberately avoids the much used, abused, and argued over term 'comparative literature' and adopts the much safer term 'comparing literature'. Although many students of literary theory will see this as a 'neglection of duty' it is a deliberate policy to avoid entering into the debate. However, if pushed, it is perhaps noticebale that the form the tutorial takes, at its most simplistic level, is similar to the 'American School', but at the same time at odds with it as the discussion of 'nationality' is central to the way the tutorial progresses. To remind readers of what is meant by the 'American School' I repeat the often used definition by Henry Remak in Stallknecht and Frenz (eds.) Comparative Literature: Method and Perspective (1961), p. 3:

Comparative Literature is the study of literature beyond the confines of one particular country, and the study of the relationships between literature on the one hand, and other areas of knowledge and belief, such as the arts...In brief, it is the comparison of one literature with another or others, and the comparison of literature with other spheres of human expression

We should also bear in mind the following definitions:

- Comparative Literature: 'The examination and analysis of the relationships and similarities of the literatures of different peoples and nations.'

- Weltliteratur: 'A term coined by Goethe which means...that literature which is of all nations and peoples, and which, by a reciprocal exchange of ideas, mediates between nations and helps to enrich the spirit of man.'

Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms

I will leave it to the individual reader to choose if they wish to pigeon-hole the activities of this tutorial under one title or another.

Initial Considerations

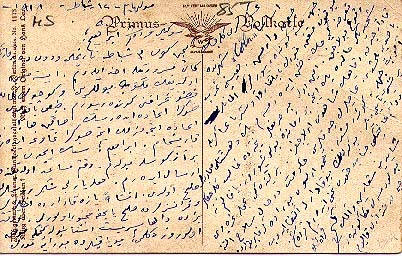

The following card was written by a Turkish soldier stationed somewhere in Europe (possibly on the Russian front). Turkey had joined the Central Powers (i.e. Germany and Austria-Hungary) in its fight against the Allies when Russia declared war on it on November 2nd 1914, followed by Britain and France on November 5th of the same year. In other words, regardless of its political ambitions, Turkey did not declare war on the Allies itself. The Turkish soldier was often vilified in Allied propaganda and looked upon as uncivilised (e.g. see the cartoon from The Grey Brigade, a trench newspaper published in 1915). Yet in the postcard below (translated from the Turkish by Celia Kerslake, University of Oxford) the soldier, by the name of Kerem, expresses emotions that would be all too familiar to Western writers - longing for his family, hope for peace, fear of future fighting, love of small comforts, and so on

Front of postcard

Reverse of postcard containing Turkish writing

Mulheim, 12 February 1918

My dear brother Ibrahim,

I was delighted to receive your [letter?] of 3 February the other day, and yesterday a card from you. I'm sending the stamps you asked for, and a photograph of little Kemal. Of course, you'd better make sure you send it [or them?] back when you've looked at it [or theml. Don't try to get away with not leffing me have it [or them] back. If you do, we'll have a row, and I won't be responsible for the consequeances. Ibrahim, I've found a bit more thick leather for you. I'll send it to you when I have time.

Praise and thanks be to God, there's been a peace agreement with the Russians as well. God willing, by the summer the British and French too will be forced to make peace. Then we'll be able to get through to Istanbul more easily, won't we?

Turkish troops are going to be coming here soon. Actually there are said to be lots of them in the city of Cologne. They're sending them all to the western front. The Germans are going to go on to the offensive with all the allied Turkish, Bulgarian and Austrian troops.I think we're going to have a really fearsome fight. You can be sure that these chaps will win at the end of the day. At the moment we're very close to confrontation. I wonder how many battles we shall see.

The workers' strike in Berlin has been suppressed. The government immediately conscripted most of the rebels and sent them to the front. Thank goodness there was no such action in the factories here.

Contenting myself with this much for today, I pray God for the continuance of your good health, brother.

Your brother Kerem [or Kerim?]

If you should find any more saccharin [?] and bread, send them to me. I'll be very grateful to you.

Acknowledgements

I am extremely grateful to several people for providing me with permission to reuse their material for this tutorial. In particular I would like to express my thanks to:

- Anvil Press Poetry Ltd for granting permission to use the translation of 'Gala' by Oliver Bernard in Apollinaire: Selected Poems (Anvil Press Poetry, 1986)

- Patrick Bridgewater to reuse his translation of Alfred Lichtenstein's 'Leaving for the Front'

- Michael Hamburger to reuse his translations of 'Grodek', and 'Battlefield'

- Rob Evans for his translation of 'Breaking Camp'

If you are interested in finding out more about these poets and others then the following books and web sites are recommended.

Further Reading

General

- Cross, T. (ed.) The Lost Voices of World War I: An International Anthology of Writers, Poets, and Playwrights (Bloomsbury, 1998). One of the finest collections of poems and prose covering a range of nationalities. The only link being that the writer in question died during the War. Each selection is preceded by an excellent study of the writer and a select bibliography.

- Giddings, R. The War Poets (Bloomsbury, 1988). A very approachable book, which concentrates predominantly on the English poets but does include poems from other nationalities.

- Silkin, J. (ed.) The Penguin Book of First World War Poetry (Penguin, 1996, 2nd ed. rev.). Silkin's anthology was one of the first of many collections to include poems from non-English writers (although all in translation).

Wilfred Owen ('An Imperial Elegy')

See the Wilfred Owen Collection.

August Stramm ('Battlefield')

- Bridgewater, P. The German Poets of the First World War (Croom Helm, 1985)

- Cross (1998), pp. 124–43

Ernst Stadler ('Breaking Camp')

- Cross (1998), pp. 101–08

- Hamburger, M. A Proliferation of Poets (Carcanet, 1983)

Guillaume Apollinaire ('Gala')

- Cross (1998), pp. 200–06

- Hyde Greet, A. Calligrames, poèms de la paix et de la guerre (University of California Press, 1980)

Georg Trakl ('Grodek')

- Cross (1998), pp. 112–123

- Graziano, F. (ed.) Georg Trakl (Carcanet, 1984)

Alfred Lichtenstein ('Leaving for the Front')

- Bridgewater (1985)

- Cross (1998), pp. 154–165

- Hamburger (1983)