Dulce Et Decorum Est: Create Your Edition

You have now had an opportunity to look at all manuscripts and typescripts, and should have reached a decision on which one is to be your base manuscript. Your task now is to create the edition itself.

Before you start, use the above tabs to:

- Familiarise yourself with transcription notation

- Read through our brief example edition

Use the below manuscripts, this time with their diplomatic transcripts alongside, to create an edition. You should start with the transcript of your base manuscript and then make appropriate edits, ensuring to note the different manuscript variations at the bottom, to create an edition of the poem you think suits best.

When looking at the manuscripts you think MS B is the ‘base manuscript’ the nearest to the final version the poet managed. Select MS B and on the right hand panel you will see a diplomatic transcription where everything on the manuscript is recorded. Copy and paste the text into a word-processor. Now, using the methods outlined in ‘Diplomatic Transcripts’ and ‘Example Edition’ work through the other manuscripts – starting with MS A – and record down any things that are different (‘variants’). Think of the following questions:

- Does any of it make you question your choice of base manuscript?

- Piecing it together can you suggest an order in which the manuscripts were written?

- What does it tell you about the poet and how they wrote a poem, how much thought they put into words and phrases?

- What did they change and why?

When you are finished working through all the manuscripts and recording the variants you will have created your own edition of this famous poem! You can then scroll below to compare to the published edition.

Diplomatic Transcription

In the transcripts below we have tried to remain as faithful to what you will see as possible, this is termed a 'diplomatic' transcription. Some notation which you may not be familiar with.

- [..] indicates that something has been deleted

- \ .. / indicates that something has been inserted or written over an original text (a palimpsest)

- \...\ indicates a marginal insertion to the left, and /... / to the right

- // indicates a page break.e.g.

- p[?]\a/in[?]\ed/ - means a letter 'p' followed by something crossed out which is unclear (hence the ?), over which an 'a' is written, followed again by an unclear deletion, over which 'ed' is inserted.

Your task is to check through the transcription of the base manuscript, and tidy it up as you think would best suit your edition. You may want to alter the punctuation; you may want to remove any text which you think is superfluous to the poem itself. Once you have done this at the bottom of your edition you will need to record the variants in the other manuscripts (i.e. the two you have not chosen for your base text).

Example Edition

To illustrate how you would do this let us choose the first two lines of a nursery rhyme which hypothetically only survives in three manuscripts (X, Y, and Z)

Manuscript X

Mary had a little lamb

Its fleece was white as snow

Manuscript Y

Mary had a small lamb

Its fleece was white as ice

Manuscript Z

Mary hid a little lamb

Its fleece was white as ice

Let us assume that we have looked at all the manuscripts and concluded that MS X will be our base manuscript. We then need to collate the variants held in Y and Z. In theory our sample edition could look like:

Mary had a little lamb

Its fleece was white as snow

Variants: Line 1 - had] hid, MS Z; little] small, MS Y. Line 2 - snow] ice, MSS Y and Z.

To read this we could say 'Mary had a little lamb' is our accepted text but we have noticed the following variants: On line 1, the base manuscript has 'had' (indicated by being to the left of the ']') whilst Manuscript Z has 'hid'. Furthermore, on line 2 the base manuscript has 'snow' whilst both Y and Z have 'ice'.

In other words, we have the base text at the top of the page and we list the variants in the other manuscripts at the bottom. The system of noting variants via ']' is not set in stone, and many editors may employ a different practice. However, the important rules to note are:

Note all variants that you think are of significance

Be consistent with your notation scheme

Explain your editorial method, e.g. 'The base manuscript is X.'

Variants from other witnesses are noted at the bottom of the page, with the word in the body text placed to the left of ']' and the variant(s) to the right.

Browse Diplomatic Transcripts of 'Dulce et Decorum est'

|

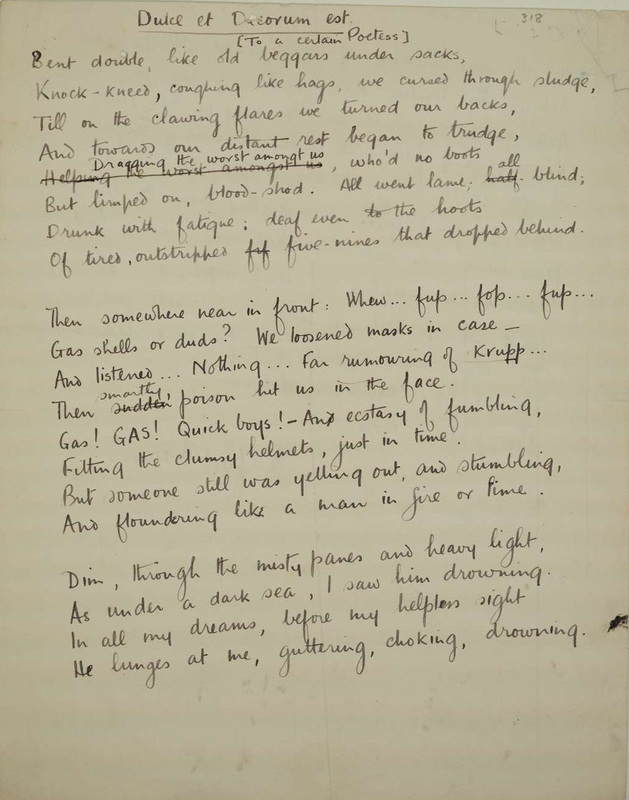

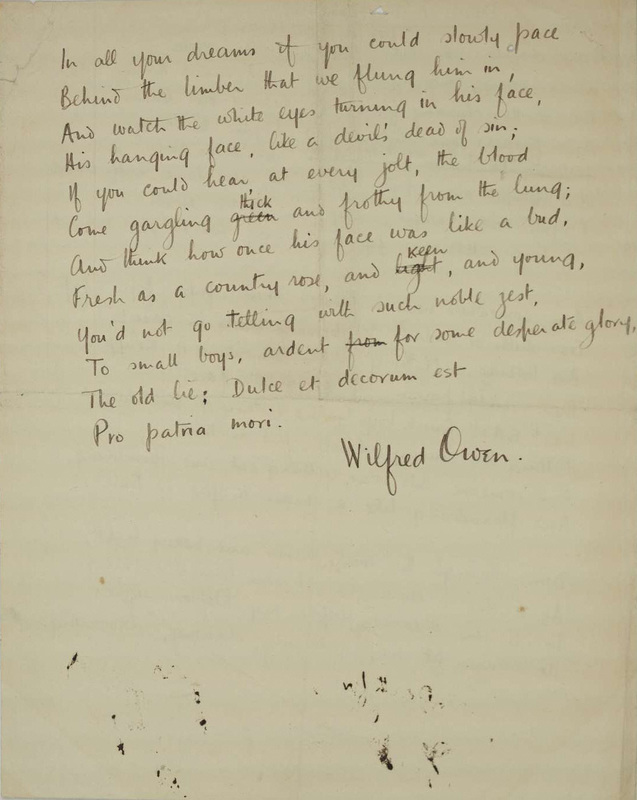

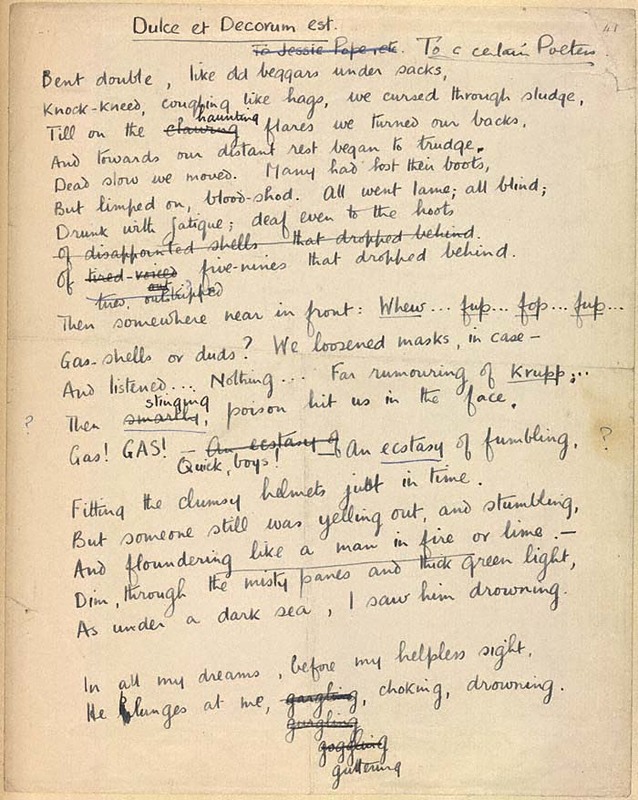

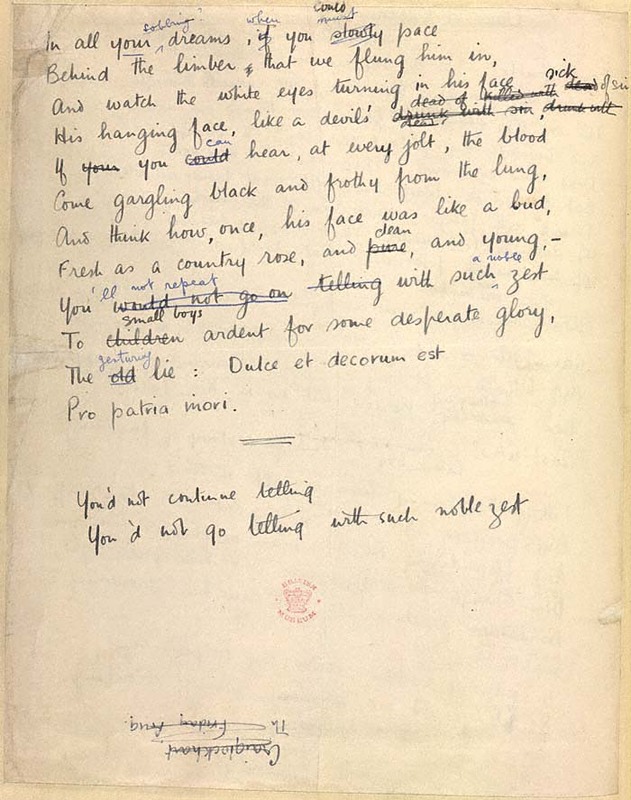

Dulce et Decorum est. [To a certain Poetess] Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Then somewhere near in front: Whew... fup... fop... fup... Dim, through the misty panes and heavy light, In all your dreams if you could slowly pace Wilfred Owen |

> > |

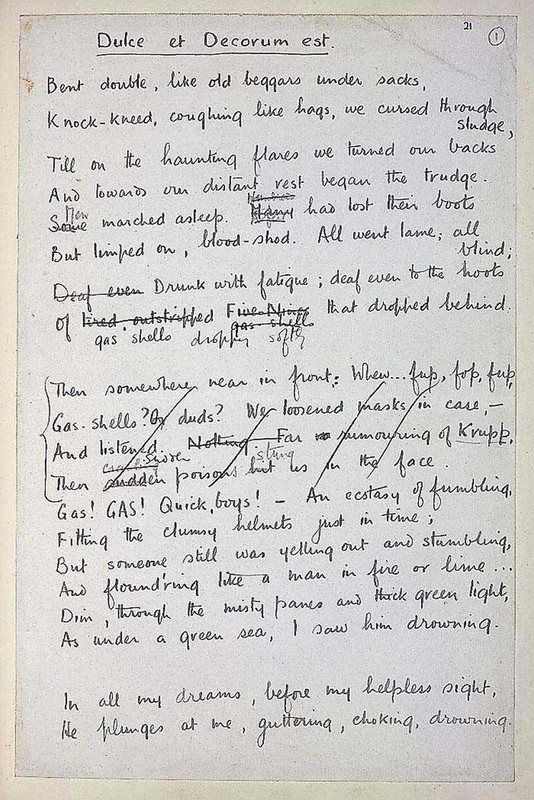

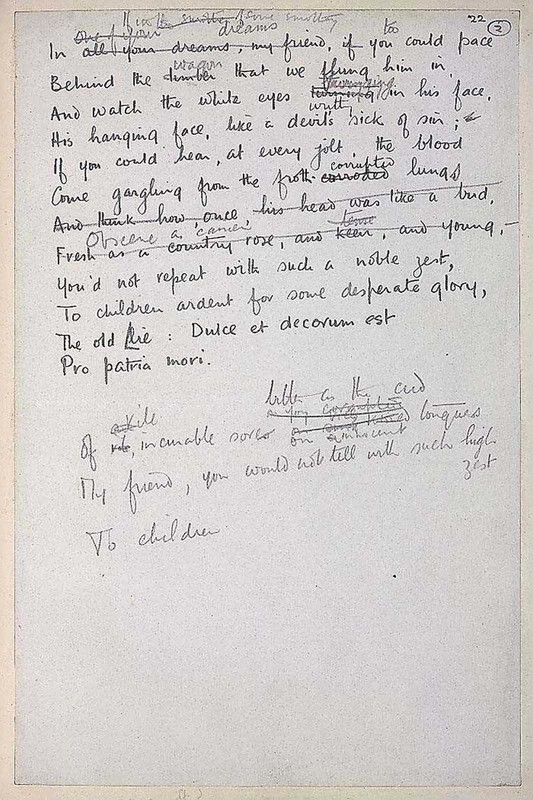

Dulce et Decorum est. Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! - An ecstasy of fumbling, In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, If in of some smothering dreams, you too could pace |

|

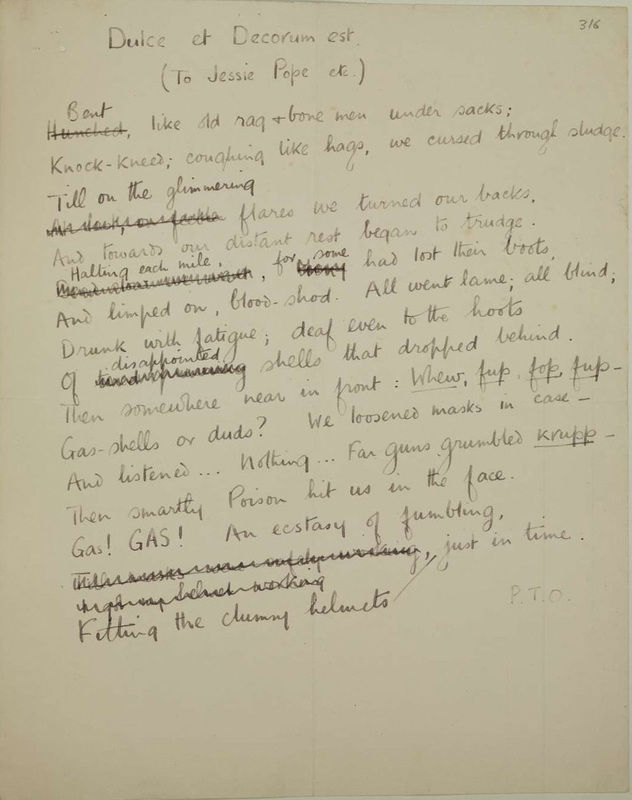

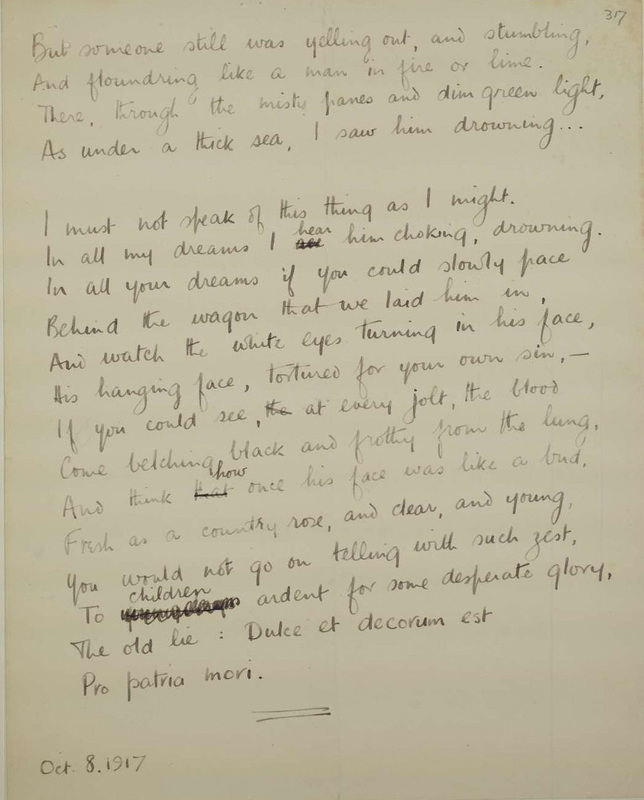

Dulce et Decorum Est Bent, like old rag & bone men under sacks; Then somewhere near in front: Whew, fup, fop, fup - I must not speak of this thing as I might. Oct. 8. 1917 |

|

Dulce et Decorum est. To a certain Poetess. Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Then somewhere near in front: Whew... fup... fop... fup... In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, In all your sobbing? dreams, when you must pace |

Compare your Edition

You can now compare your edition with a published one (Stallworthy, 1983) and read some information about the manuscripts and the decisions Stallworthy made in creating his edition.

DULCE ET DECORUM EST

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! - An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, -

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.(p.140)

Seminar Conclusion

In the course of this tutorial the manuscripts have been referred to as A, B, C, or D. In reality they are:

- A - Oxford English Faculty Library, Box 2, p. 318 and verso B - British Library, MS Add. 43720, pp. 21 and 22 C - Oxford English Faculty, Box 2, pp. 316 and 317 D - British Library, MS Add. 43721, f. 41 recto and verso

- Jon Stallworthy in his edition of 1983 used MS B as his base manuscript. He notes on p.140 of Volume I of his edition:

- Drafted at Craiglockhart in the first half of October 1917...this poem was revised, probably at Scarborough but possibly at Ripon, between January and March 1918. The earliest surviving MS is dated 'Oct. 8. 1917.'.

- Stallworthy notes that there is a particular problem with line 8 as Owen, even in the latest draft, never settled on the final line. Sassoon (1920) and Blunden (1933) both read this line as 'Of gas-shells dropping softly behind' even though they too are taking MS B as their base, but it is not until Day Lewis (1963) that there is the first occurrence of the line 'Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind' (retained by Hibberd, 1973).

- British Library, MS Add. 43721 is notable for containing additions and alterations by Sassoon. These occur predominantly near the end of the poem and are written in blue.

Author: Dr. Stuart Lee, 2009; Revised 2021