Intro to WW1 Poetry: Edward Thomas

Biography

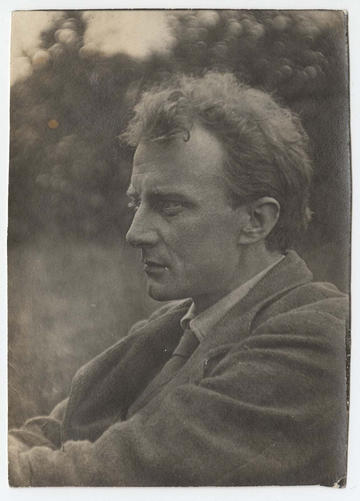

Image © The National Library of Wales/ The Edward Thomas Literary Estate

Edward (Philip) Thomas was born in Lambeth, London, of Welsh descent and he was educated at St Paul's college and then Lincoln College at Oxford University (where he studied history). A prolific writer of prose (including biographies of Richard Jefferies, Swinburne, and Keats), and a moderately successful journalist, he began writing poetry in 1912 under the pseudonym Edward Eastaway, but did not devote himself fully to the medium until 1913 after a meeting with Robert Frost, the American poet, who by then was living in England.

Thomas enlisted in 1915 with the Artists' Rifles as a private but was killed two years later at Arras having achieved the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. His poems include some of the most noted pieces from the genre, capturing the love of the English countryside unlike any other.

Biography by: Dr. Stuart Lee, 1997

A Private

This ploughman dead in battle slept out of doors

Many's a frozen night, and merrily

Answered staid drinkers, good bedmen, and all bores:

'At Mrs Greenland's Hawthorn Bush,' said he,

'I slept.' None knew which bush. Above the town,

Beyond 'The Drover' a hundred spot the down

In Wiltshire. And where now at last he sleeps

More sound in France - that, too, he secret keeps.

Poems of the First World War: 'Never Such Innocence', ed. Martin Stephen (Everyman, 1995), p. 164

Literary Criticism of 'A Private'

-

A Private (title)

The anonimity of the central character of the poem is established by simply calling the poem 'A Private'. Thomas then is not writing a memorial poem to a certain person, but rather to the multitude of dead. Nevertheless he fills the poem with personal details giving character to the dead soldier. -

'This ploughman' (L.1)

The ploughman is an important figure to Thomas, representing his love for the country and in particular, England (see also the appearance of the ploughman in 'As the Team's Head Brass').Thomas's admiration for the countryside is well-documented, but a couple of examples will serve to illustrate this. In his essay 'England' he praises Izaak Walton's (1593–1683) The Compleat Angler as 'a book that filled me so with a sense of England...I touched the antiquity and sweetness of England - English fields, English people, English poetry, all together' ( The Last Sheaf: Essays, Edward Thomas (J. Cape, 1928), p.109.). In 1915 he compiled an anthology entitled This England in which he claims 'I wished to make a book as full of English character and country as an egg is of meat'.

-

''Many's a frozen night" (L.2)

This mirrors the frozen nights spent in the trenches by the ploughman (and Thomas of course). -

"The Drover" (L.6)

By giving the detail of the pub's name, Thomas adds personality to the dead ploughman. -

''where now...he secret keeps" (L.7 & 8)

The ending is serene, with the long vowels of the rhyming 'sleeps' and 'keeps' adding to the calm. There is no bitterness here as one would find in Sassoon or Owen - the sleep of the ploughman is 'sound' and secret.

As the Team's Head-Brass

As the team's head-brass flashed out on the turn

The lovers disappeared into the wood.

I sat among the boughs of the fallen elm

That strewed the angle of the fallow, and

Watched the plough narrowing a yellow square

Of charlock. Every time the horses turned

Instead of treading me down, the ploughman leaned

Upon the handles to say or ask a word,

About the weather, next about the war.

Scraping the share he faced towards the wood,

And screwed along the furrow till the brass flashed

Once more.The blizzard felled the elm whose crest

I sat in, by a woodpecker's round hole,

The ploughman said. 'When will they take it away?'

'When the war's over.' So the talk began -

One minute and an interval of ten,

A minute more and the same interval.

'Have you been out?' 'No.' 'And don't want to, perhaps?'

'If I could only come back again, I should.

I could spare an arm, I shouldn't want to lose

A leg. If I should lose my head, why, so,

I should want nothing more...Have many gone

From here?' 'Yes.' 'Many lost?' 'Yes, a good few.

Only two teams work on the farm this year.

One of my mates is dead. The second day

In France they killed him. It was back in March,

The very night of the blizzard, too. Now if

He had stayed here we should have moved the tree.'

'And I should not have sat here. Everything

Would have been different. For it would have been

Another world.' 'Ay, and a better, though

If we could see all all might seem good.' Then

The lovers came out of the wood again:

The horses started and for the last time

I watched the clods crumble and topple over

After the ploughshare and the stumbling team.

Poems of the First World War: 'Never Such Innocence', ed. Martin Stephen (Everyman, 1995), pp. 165–6

This is No Case of Petty Right or Wrong

This is no case of petty right or wrong

That politicians or philosophers

Can judge. I hate not Germans, nor grow hot

With love of Englishmen, to please newspapers.

Beside my hate for one fat patriot

My hatred of the Kaiser is love true:-

A kind of god he is, banging a gong.

But I have not to choose between the two,

Or between justice and injustice. Dinned

With war and argument I read no more

Than in the storm smoking along the wind

Athwart the wood. Two witches' cauldrons roar.

From one the weather shall rise clear and gay;

Out of the other an England beautiful

And like her mother that died yesterday.Little I know or care if, being dull,

I shall miss something that historians

Can rake out of the ashes when perchance

The phoenix broods serene above their ken.

But with the best and meanest Englishmen

I am one in crying, God save England, lest

We lose what never slaves and cattle blessed.

The ages made her that made us from dust:

She is all we know and live by, and we trust

She is good and must endure, loving her so:

And as we love ourselves we hate our foe.

Poems of the First World War: 'Never Such Innocence', ed. Martin Stephen (Everyman, 1995), pp. 72–3

Rain

Rain, midnight rain, nothing but the wild rain

On this bleak hut, and solitude, and me

Remembering again that I shall die

And neither hear the rain nor give it thanks

For washing me cleaner than I have been

Since I was born into this solitude.

Blessed are the dead that the rain rains upon:

But here I pray that none whom once I loved

Is dying to-night or lying still awake

Solitary, listening to the rain,

Either in pain or thus in sympathy

Helpless among the living and the dead,

Like a cold water among broken reeds,

Myriads of broken reeds all still and stiff,

Like me who have no love which this wild rain

Has not dissolved except the love of death,

If love it be for what is perfect and

Cannot, the tempest tells me, disappoint.

The Penguin Book of First World War Poetry, ed. Jon Silkin (Penguin Books, 1981), p. 95