Exercise III: Why do we remember the war in this way?

Our remembrance is shaped by many factors. Some have developed slowly over the 90 years since the War, others more recently (in the 1960s for example).

Dan Todman (2005) provides a lengthy list of cultural and social events which he feels has shaped the memory of the War in terms of it being perceived as futile or horrific, with needlessly excessive casualties. These include:

- the shaping of remembrance by bereaved parents to focus on the dead

- the compliance with this by the nation out of respect, thus diminishing any thoughts of celebrating a victory

- the plethora of war books in the late 1920s and 1930s which often focussed on the harsh realities of trench warfare

- attitudes in the Second World War to compare that conflict (i.e. meaningful, better led and fought) against the perceived disasters of 1914-1918

- the prominence of the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon which stressed futility, pity, suffering, the horror, incompetence

- the screening in 1964 of the BBC’s The Great War series which, scripted in part by John Terraine, presented a predominantly negative view of the war and the generals

- the publication of Alan Clark’s The Donkeys in 1961 which, though riddled with inaccuracies, cemented the view of incompetent generals

- the popularity of Joan Littlewood’s Oh! What a Lovely War (though Todman suggests this was as much a product of the accepted viewpoint that had developed in the 1960s as a shaper of attitudes), and the 1969 filmed version by Richard Attenborough

- publication of Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory in 1975, again a highly influential book, but historically inaccurate

- the screening of the BBC’s The Monocled Mutineer in 1986 which again depicted the negative side of the war

- the screening of the BBC’s Blackadder Goes Forth in 1989

- later war novels such as Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, Sebastian Faulks’s Birdsong, Susan Hill’s Strange Meeting

Todman (2005, pp. 224-226) also identifies five generations who have shaped remembrance of the war:

- The parents of those who fought and died in the conflict who exerted a powerful influence on the public in terms of focusing on the sacrifice. However, they would not have viewed the war as futile or mistaken. This generation gradually disappeared during the 1950s.

- The generation who had fought in the war and survived. Their attitudes were undoubtedly varied, and often remained hidden until the 1960s when historians began to take an interest in recording their views. However, by then their memories had possibly become blurred or shaped by what they thought people ‘expected to hear’. These veterans began to die off in the 1970s and throughout the 1980s, and only a handful remain.

- The children of those who fought in the war (born as late as the 1930s). When they became adults they were the generation who wrote the books, plays, and television series that became so popular from the 1960s onwards. They are probably the most important for shaping the ‘myth’ of the war.

- The grandchildren of those who had fought in the war. They shared memories with their grandparents in the 1960s which perpetuated the memory and shaped reactions to the war in the 1980s and 1990s.

- The great grandchildren of those who had fought in the war. For the most part they will have had no contact with veterans and have no personal connection to it, but they provided the audience for Blackadder and the readership for Birdsong.

Does this ring true to you? Does this explain how remembrance was shaped?

Now, read the following essays below before you proceed:

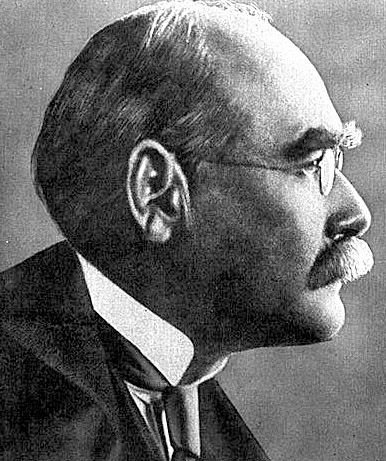

Rudyard Kipling, Image © Public Domain

Rudyard Kipling, Image © Public Domain

Following the Armistice, thoughts naturally turned to remembrance, namely remembering the conflict and remembering the dead. We must, however, remember that grievance was universal, affecting all the countries involved – not just Great Britain and the Empire.

For most grieving relatives local or national symbols (such as War Memorials, or Remembrance Day – see below) offered some focus for their loss. In Britain it had been decided not to bring back the bodies of the fallen, but to bury them in cemeteries with their comrades near to where they lay. Some relatives did make the trip to France and Belgium, so called ‘battlefield pilgrimages’, assisted by St Barnabas tours who offered subsidised travel and accommodation. Rudyard Kipling, in his short story ‘The Gardener’, attempts to capture the feelings of the bereaved:

‘Michael had died and her world had stood still and she had been one with the full shock of that arrest. Now she was standing still and the world was going forward, but it did not concern her – in no way or relation did it touch her…the Armistice with all its bells broke over and passed her. At the end of another year she had overcome her physical loathing of the living and returned young, so that she could take them by the hand and almost sincerely wish them well.’ (Kipling, 1990, p. 315).

In the story the main protagonist – Helen Turrell – eventually finds consolation when she locates the grave of her son with the assistance of a Christ-like gardener figure. It should be noted, never truly came to terms with the death of his son – John Kipling – at the Battle of Loos. His work on the history of John’s regiment, the Irish Guards, and on the war cemeteries is a testimony to his grief. He also, like many others, became interested in ‘Spiritualism’.

For a sarcastic view of battlefield tours, see the prescient poem High Wood by Philip Johnstone written in 1918

The Imperial War Museum, the Unknown Soldier, and Remembrance Day

Imperial War Museum, Image © Public Domain

Imperial War Museum, Image © Public Domain

In 1917, the Imperial War Museum was opened in London to collect material from the then ongoing conflict, both for educational and heritage purposes, but also to remind people of the suffering. In a sense, it too became a focus for remembrance. It moved to its current location in 1936.

In 1920, the body of the unknown soldier (randomly selected from the corpses of unidentified British soldiers) was buried with full military honours in Westminster Abbey. The ceremony itself attracted vast crowds. Bereaved relatives, who had lost someone in the war but for which no body had been found, could again use this as a focal point. It could, after all, be their son, father, or brother, being buried in London.

The clearest focus for remembrance was, and still is, the 11th November – Remembrance Day – the date of the Armistice. For many years after the war a two-minute silence was remembered on that day, with people dressing in mourning, and the nation’s attention drawn to the Cenotaph in London or the local war memorials that had been commissioned in towns and villages around the country. However, after the Second World War, when the date of the Armistice in 1918 was not significant to the more recent conflict, Remembrance Sunday was established; yet its date – the nearest Sunday to November 11th – still drew focus back to the first conflict.

Veterans, i.e. those who had fought in the war, though they remembered their fallen comrades also wanted to celebrate the comradeship they had experienced, and to a certain degree the victory over Germany. Annual reunions were common amongst regiments, and the Albert hall originally played host to a Remembrance Ball, only later changing to the Remembrance Service after it was felt it demonstrated a lack of sensitivity to the fallen and more importantly the bereaved parents left behind. Indeed, gradually these ‘celebrations’ disappeared altogether, viewed as tactless and insulting, and were replaced by restrained ceremonies of religious and spiritual significance.

Indeed the sense of mourning, as opposed to victory, holds the most power in terms of shaping remembrance. Although by the mid-1920s many people were moving on with their lives, each November 11th the nation returned to remembering the dead and, as Dan Todman notes (2005, p. 58):

‘It became [remembrance] … something that you did for others, not yourself: a social obligation rather than an emotional necessity’

War Memorials

The construction of war memorials was an important act of remembrance for many nations. Again we must recall that Britain was not alone in this activity, and that war memorials survive in many countries. Look at the two images below.

Here we have memorials reflecting two opposing nations in the Balkans. Not only does this demonstrate the universality of grief, it points to key differences. The Bulgarian war memorial dates the war as being from 1915-1918; the Serbian war memorial is dedicated to France. Why might this be so?

Bulgarian War Memorial (modern photograph), Image © The Great War Archive, University of Oxford / Stuart Lee

Bulgarian War Memorial (modern photograph), Image © The Great War Archive, University of Oxford / Stuart Lee

Serbian War Memorial (modern photograph), Image © The Great War Archive, University of Oxford / Stuart Lee

Serbian War Memorial (modern photograph), Image © The Great War Archive, University of Oxford / Stuart Lee

[Answers: Bulgaria entered the war in 1915 on the side of the Central Powers, encouraged by the failures at Gallipoli. Serbia was aligned with the Allies, but faced the might of Austro-Hungarian, German, and Bulgarian offensives. French troops were sent to assist the Serbs.]

Jay Winter (1995, p. 51) notes:

‘War memorials are collective symbols. They speak to and for communities of men and women. Commemoration also happened on a much more intimate level, through the preservation in households of possessions, photographs, personal signatures of the dead. That is why it mattered so much to parents to retrieve the kit of their sons after notification of their deaths.’

He goes on to observe (1995, p. 79):

‘War memorials inhabit three distinctive spaces and periods: first, scattered overt the home front before 1918; second in post-war churches and civic sites in the decade following the Armistice; and third in war cemeteries.’

In Britain war memorials performed a dual purpose. Not only did they provide a symbol of remembrance, they also represented a focal point for grieving relatives who could not visit the grave (assuming there was one) of their relative. Britain had decided not to repatriate the bodies of the fallen, and instead created a series of cemeteries throughout France and Belgium where the dead were buried. Although this did not pass without some discussion, in retrospect the collective graves where comrades lie together, with no attempt to distinguish (in terms of the shape or size of the headstone) between the ranks, seems fitting and has a profound effect on visitors.

Local war memorials, therefore, created a focal point in the city, town, or village for grieving relatives to visit when they chose, especially on Remembrance Day (11th November). There is now a National Inventory of these war memorials. Possibly the most famous memorial is the Cenotaph (or ‘empty tomb’) in Whitehall. This was originally designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens as a temporary memorial for the Victory parade through London of the 19th July, 1919. However, the impression it left on the nation was profound and a permanent version replaced the temporary one. It is this that is still the main focal point at every Remembrance Sunday where soldiers and veterans march past, and members of the Royal Family and politicians lay their wreaths.

At the sites of the major battles themselves, larger memorials were erected. The Thiepval memorial on the Somme commemorates the 600,000 allies who died there, and inscribed on its walls are the names of the 73,000 men whose bodies were never recovered. Similarly the reconstructed Menin Gate in Ypres acts as a memorial to the fallen in the battles that raged throughout the salient.

We should also remember that the war cemeteries themselves also acted as a memorial. Now immaculately maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves commission these exude serenity and calm. The dead are buried in neat rows of identical white headstones, only differing slightly in the inscription, with no distinction made between Officers and other ranks. Often each will contain a Great Stone of Remembrance (a large white altar) with the inscription ‘Their name liveth for Evermore’ (chosen by Rudyard Kipling), and a Cross of Sacrifice.

Spiritualism

The process of grieving is a complicated matter, and on such a massive scale as the death toll incurred in 1914-1918 it is unsurprising that not everyone could come to terms with their loss, or comprehend the separation. Conventional religions did not seem to offer enough, nor was sufficient solace found in the national acts of Remembrance.

A noted phenomenon then, during and after the war, was the remarkable growth in spiritualism – labelled, at the time, as a science. The belief that there is life after death is common to many religions, notably Christianity which was the dominant religion in Britain at the time, but spiritualism went further than that. Whilst attempting to explain the afterlife in pseudo-scientific terms, it also suggested that it was possible to contact the dead, and more interestingly (in terms of religious belief at the time which viewed such acts as heretical) it encouraged it.

Although spiritualism had existed long before the war (indeed communicating with the dead, or attempting to goes back to Biblical times and beyond); the aftermath of the 1914-1918 conflict, and the mass grief it engendered, saw a very public rise in the popularity of mediums, séances, and similar. New ‘academic’ journals appeared and the movement attracted notable public figures such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Rudyard Kipling (who had both lost a son in the war) – though Kipling’s treatment of the subject is ambivalent at best.